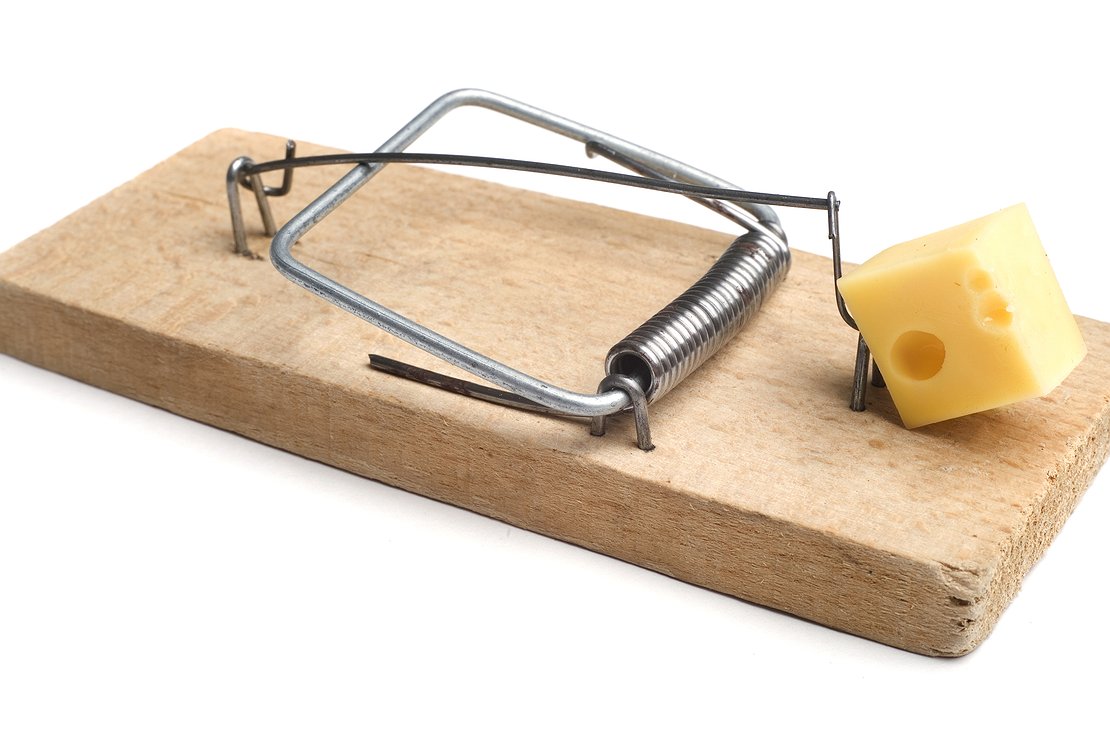

Civic anarchism:The Constitutional State As a Trap

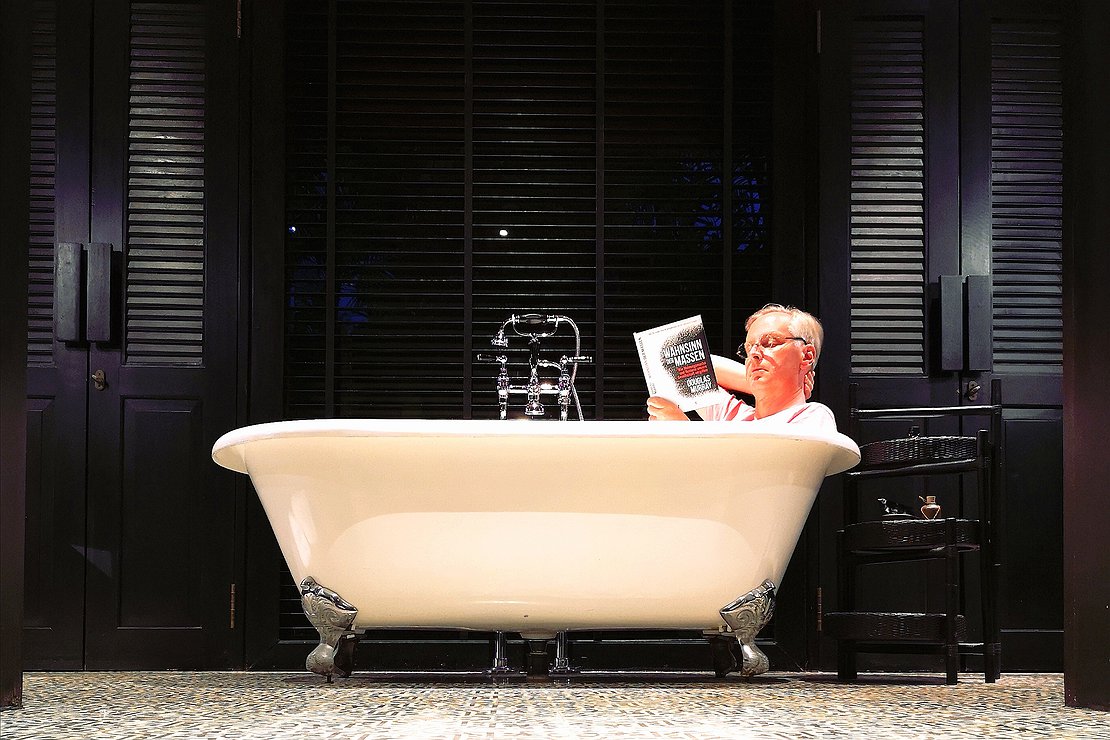

The Spanish central government had lured him into a veritable trap, said Carles Puigdemont, the hounded Catalan regional president, at that time still at large in Belgium. Because when, after the secession plebiscite, he had started last autumn to work towards declaring his region’s independence in the Catalan Parliament, Madrid had pretended to be an honest dealer. So he waited with the declaration of independence, but then soon realized that the central government's willingness to negotiate had only been a pretence, and now had issued an arrest warrant instead.

Then Carles Puigdemont said something interesting: Such behaviour does not befit a constitutional state under the rule of law! This is interesting because Puigdemont’s outrage about the central government’s deviousness may be understandable – after all, one expects fair and transparent behavior of a democratic constitutional state in the 21st century. But on the other hand, this very expectation is wrong: Setting traps is typical for the so-called constitutional state; strictly speaking, it is nothing more than a big, constitutionally institutionalized trap.

Because traps are characterised by the fact that the victim enters it unsuspectingly, and only becomes aware of it when it wants to get out again and can no longer do so. The trapper behaves accordingly: until the victim falls into the trap, he remains inconspicuous and friendly. But once the victim is in and desperately trying to get out, the trapper beats it, makes the trap a definite prison or, if need be, drubs his victim to death.

That's pretty much the history of the constitutional state, which initially appeared very pleasant: Contrary to the absolutist monarchy with its arbitrary seizure of its subjects, the authorities themselves should now be subject to the law. Or as a representative of the Scottish enlightenment said: Instead of Rex-Lex (first the king, only then the law), now the reverse should be the case: Lex-Rex. To reinforce this point, an English king in the 17th century, and a French king in the 18th century, were beheaded.

This was – consciously or unconsciously – a symbol of a social order, which had at the top of the hierarchy not a head, but the law, to which everyone is subject, not just the little guys, but also the big ones, not only the weak, but also the strong, not only private entities, but also the state. Immanuel Kant bolstered this philosophically by demanding legal norms that are validated not by a ruler, but by the general applicability of their content; only that which applies to everyone equally can claim validity.

Of course, the authorities did not like it, but they had no choice but to at least pretend that they were subject to the law. And this purpose was served by the so-called ‘constitutional state,’ to which people flocked enthusiastically, not anticipating the trap they were getting in to. For the law, which they hoped would control the authorities, was created by none other than these authorities themselves. No wonder that these soon mounted no less than two worldwide wars, industrial extermination camps, torture chambers and devious state headquarters, which above all dislike one thing, namely when people or whole regions want to break out of the trap of this unjust state – as for example Carles Puigdemont, or rather Catalonia.

Translated from eigentümlich frei, where the original article was published in issue no. 182, May 2018.